A conversation with Jonathan Faiers

In August last year, The Wall Street Journal reported that the younger generation was shunning hand-me-down furs. Titled 'The Awkward Heirloom: No One Wants Grandma's Fur Coat' through the tale of Gina Radke and her 84-year-old grandmother Helen Webb the piece wrestles with the complexities of owning and wearing fur in a time when animal rights lobbies have campaigned against it, even if it's vintage.

I could relate. My grandmother gave me her fur coat about 12 years ago. I used to wear it in London, but the first time I wore it in New York, a woman took me aside on a subway platform and warned me that many people were anti-fur in New York. I felt self-conscious and put it away for a few months. Then I decided to give it another go, gingerly slipping it on to walk to my sister's house. Ten minutes in, I felt good, the air was crisp, I was walking with a festive spring in my step—it was December. Then on Third Avenue, outside H Mart grocery store, a man locked eyes with me and screamed, at the top of his voice, "You are fucking ugly." I haven't worn the coat since.

The move against fur has quickened pace over the last few years; in 2017, Vogue Paris, who famously stuck their middle finger up to fur protesters in a Mario Testino shoot from the August 2008 issue, announced it would no longer shoot real fur. It did so with a cover featuring Gisele Bündchen wearing a faux fur coat—pelts have been replaced with a booming market for synthetic furs. Fashion brands such as Gucci and Prada have also denounced fur. Israel has become the first country to ban the sale of fur, and California is the first state in America to ban the sale, donation, or manufacture of new fur.

This week I spoke to Jonathan Faiers, professor of fashion thinking at Winchester School of Art University of Southampton and author of the book Fur: A Sensitive History published last year by Yale. For a brief overview of the book, you can read this article Jonathan wrote for the Yale blog. I was keen to ask Jonathan about the storied history of fur and why it has become such a complex site of debate—it pushes and pulls at so many issues that fall into the fashion and sustainability conversation. You have the material, animal fur and synthetic fake or faux fur, and its manufacturer, and end of life. You have the philosophical: caring for, mending, and handing down your clothes to generations to come. You also have the destruction of nature and a history of colonialism.

Thinking about these issues and the fur that languishes in my wardrobe, to accompany the article, I commissioned Chinese-born New York-based fashion photographer Gloria Gao to photograph my grandmother's coat and some other fur pieces. Featuring Constance Cooper and Dorothy Griffiths, the resulting images are eerie.

Photos by Gloria Gao, featuring Constance Cooper and Dorothy Griffiths, New York, June 2021

Shonagh: What drew you to research and write Fur: A Sensitive History?

Jonathan: As with any new project—for me anyway—it was partly a matter of coincidence. I was asked to write an essay for the Savage Beauty publication to go with the Alexander McQueen exhibition at the V&A. They asked me to write specifically on his relationship to the natural world, so a lot of what I wrote about was his use of fur and feathers.

More or less, at the same time, I was asked to interview a young, British female furrier for a fashion magazine. It was really interesting to hear her speak. I quickly realized how difficult it was to be a furrier in this day and age, particularly a younger woman furrier. It was almost impossible to talk to her or ask her anything about what she was doing; that wasn't immediately within the context of the anti-fur lobbies. We almost couldn't get beyond that. So those two projects piqued my interest.

Then at the same time, I was engaged in working on the journal I edit, Luxury: History, Culture, Consumption— with what we've termed critical luxury studies. I started to think and write about the idea of the tactile, sensory experience of luxury and how important that is, especially when a lot of work was being done on digital or virtual luxury. The real, actual physical contact with luxury seemed to be becoming almost side-lined, and in its place was this experiential virtual world. So fur, being supremely tactile, and understood as a traditional luxury item, seemed relevant to this area.

I started to look around assuming there must be loads of writing on fur. Actually, there isn't; most studies to do with Western fashionable fur is out of print. There are lots of books on indigenous fur and specific aspects of the industry and also manuals from 1950s aimed specifically at furriers. Apart from that, and one or two other studies that look at particular political aspects of fur, nothing. I thought this is interesting. I'm always intrigued by subjects that seem to be off the academic radar or are taboo for whatever reason. So I thought, Okay, I'm going to write about it. I took it to Yale, who had published me before, and they were super enthusiastic about it. So, it snowballed from there.

Shonagh: Fur has such a long history; it is thought to be the earliest form of clothing, and biblical stories write that God made garments from animal skin for Adam and Eve. Can you talk specifically about when it became a fashion or luxury item, moving away from a primitive warm, functional fabric?

Jonathan: I could spend ages talking about what we mean by "fashion," but I know what you mean—how it shifted from, as you say, just being a necessity.

What kick-started its journey to being a fashionable item or fabric are the sumptuary laws established in Europe from the 12th century and lasting until the 17th century and 18th century in some parts. These laws attempted to regulate and control the consumption and display of certain goods, typically luxury goods, notably items of dress and often fur. Fur was one of the very first objects subject to these sumptuary laws.

These laws were partly social; to maintain the class structure and make class distinctions visible. But they were also, particularly for Europe and Britain, economic and protectionist policies. The government instituted sumptuary legislation against fur to protect the native fur industry and curtail imported furs. Simply put, in the medieval period, finer, softer, rarer, and costly foreign furs such as sable, ermine, lynx, and Baltic squirrel—which is a black squirrel—were only allowed to be worn by the nobility, or those in the upper classes, who could prove that they had a certain income. While the lower classes, for want of a better term, were only allowed to wear coarser furs—such as lambskin; cony, or rabbit as we now call it; the domestic cat was often used; and fox. These laws immediately had the effect of differentiating between different classes of society by the kinds of furs permitted to be worn.

However, the laws were very complicated, and went through lots of modifications. It's tough to find out how effective they were, but there are cases of people being fined and penalized for wearing the wrong sort. With any law that tries to tell you what you can and can't wear, it immediately makes the forbidden desirable and "fashionable." What it did, in effect, was make people aspire to these finer, more fashionable types of fur. As fashion still does today, it also allowed you to transcend or move between classes or assume a different status. Today some people maybe think that buying and carrying a Hermes handbag, for example, means that they've achieved something; they've gone up in the world. I don't think you can't underestimate these laws, which seem crazy to us today. They had a real effect, and it immediately started the journey towards fashionable fur as we now understand it.

Shonagh: The idea that fur denotes wealth and status has undoubtedly remained. In the book, you talk about how throughout the 20th-century, communities, such as the Black community, would aspire to own fur coats, seeing it as a marker of success. Could you talk specifically about how these ideas about owning and wearing fur have carried through history?

Jonathan: It's interesting you pick up on the African American desire for fur. This desire for fur and what it might signify has become the subject of a kind of modern-day proscription. For many Black women in America, certainly in the early to mid 20th century, owning a fur coat was one of the few markers of status and self-esteem at a time when owning property, and other rights were forbidden to you as a Black person in many states. You could buy and wear a fur coat and feel good about yourself at least part of the time. You could also pass it on to another generation.

Without trying to put too fine a point on it, the anti-fur lobby gathered pace at around that exact moment, in the late 60s and on into the 70s. Suddenly, you get this denigration, of specific communities, including the Black community, for wearing fur. You get caricatures in films—pimps and things like that—or people of color derided for wearing fur by middle-class white anti-fur lobbies. It's complicated and very sensitive as an issue.

Coming back to your point about status, I think we still carry these desires, specifically for women. In the mid 20th century, the idea of a mink coat went along with having the ideal husband, the perfect kids, the ideal house, and the perfect car. Along with that, you needed the perfect mink coat. It was an actual endorsement. I think we still have those ideas today; they might not be the same objects, they might not be the same goals, but we still ascribe to certain kinds of ideas.

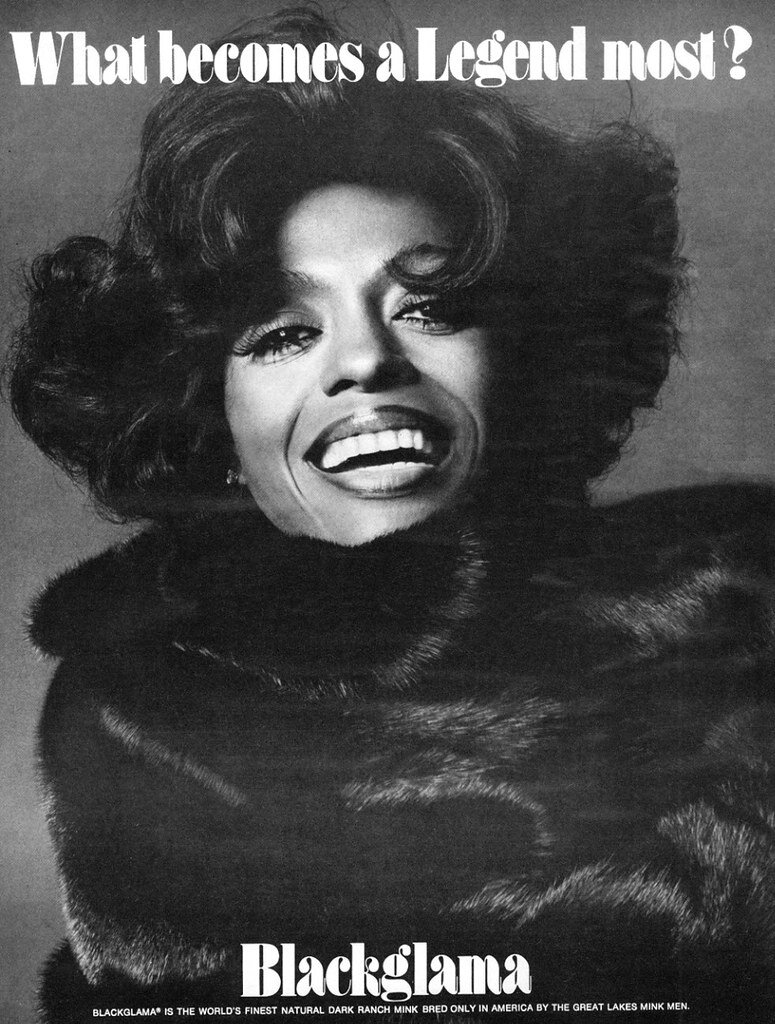

Diana Ross for Blackglama 1973. Designed by Bill King. Courtesy of Jonathan Faiers.

Shonagh: I was fascinated to learn from your book that fur is also linked to the social and economic development of North America. Can you talk a bit more about what you found?

Jonathan: As I started to research the book, I became aware of how vital the fur industry had been throughout history to various countries and cultures. The obvious one, and the one that I focus on in the book, is how the fur trade shaped what we understand today as modern North America and Canada. That's primarily due to the desire for beaver skins. The craze for beaver hats was so widespread and long-lasting that the hat-making industry had decimated the European stock by the late 16th early 17th century.

Yet the craze was still ongoing, so they had to look elsewhere for supplies, and North America and Canada had plentiful stocks of the American Beaver. That drove colonial ventures into that territory, first by French and British trappers and fur traders and then by American organizations themselves. The desire for beaver, then subsequently other kinds of pelts, really kind of shaped not only the economy of America, it certainly dictated its geographical settlement patterns.

The negative side to this exploitation was not only the near decimation of the American beaver but also the threat to the indigenous Canadian and American populations, who, for centuries, had lived and tracked alongside beavers in a much more sustainable relationship that didn't threaten the whole species. There's a very complex history between indigenous fur trappers and traders who then worked with the French and English and subsequent Americans to exploit this natural resource.

You can gauge how important the animal was because there are 1000s of place names called beaver this or that, Beaver Springs, Beaver Lake, etc. The first postage stamp in Canada was called Three-pence Beaver, and it's got a beaver on it. There are also all sorts of references to them in cities such as New York and London. If you look around at the details of architecture, you often see beavers depicted, which signifies a building associated with the fur industry in some way.

The trade made for a lot of the earliest American dynastic fortunes. The Astor family, for example, made their money through fur. The Hudson's Bay Company, originally a British institution, was instituted because of the desire for beaver. Some of the earliest pioneers of Hollywood in America come from families whose fortunes were made from fur. So something as vital as the movie industry, you could almost argue, has its origins in fur. It has had an enormous impact on geography, indigenous populations, and then, subsequently, culture.

Shonagh: When did you find that people started to protest against fur historically? Is there a point in time where people begin to care about animal rights?

Jonathan: One of the things I did get interested in when working on the book was tracing the origins of the anti-fur movement further back than PETA or Lynx, which everybody thinks about. You could argue it came about in the middle of the 19th century as part of a whole package of social issues becoming prominent. Protesting cruelty against animals has quite a long history; you can find pamphlets and things about it from the early 19th century, which goes hand in hand with the rise of vegetarianism and, ironically, things like the beginning of women's suffrage. All kinds of social issues came to prominence around the middle of the 19th century, with the formation of the Anti Vivisection Society or the societies of Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Being anti-fur, as far as I could tell; strangely enough, came out of what was known as plumage societies, or fur and feathers societies, which were organizations organized mainly by the middle class, intellectual women, who, initially, were violently opposed to the trade in bird feathers used in millinery. The craze for women wearing big hats with lots of feathers from the latter part of the 19th century caused the near decimation of several species. Some of these protest groups originally started from these plumage societies, as they were called. They would hold meetings and soirees where they would try to advocate against using animals for fashion and hold charity events to raise awareness.

Very soon after that, you get the first protests against fur, which I couldn't say definitively, but certainly some of the earliest protests are against the use of sealskin. Seal coats and jackets were one of the first fashionable full-length items where fur is used, principally on the outside. The majority of the history of fashionable fur in the West, (and I'm not talking about indigenous cultures’ use of fur) was, up until the 19th century, used primarily as edging, trimming, lining, or accessories. It was not used as an outer garment with the fur on the outside, as we would understand the fur coat today. That only happened in the latter part of the 19th century, about the 1870s or so, partly due to the increased production of fur, alongside advances in manufacturing and the growth of supplies of furs of different sorts from all over the world. One of those was the sealskin jacket which became uber fashionable; the ideal object of desire for many women was to have a sealskin jacket. Some of the first anti-fur protests were against sealskin around the 1870s; they were against the decimation of the populations of seals, mainly in the Bering Islands. But as I said, its origins grew out of a package of other kinds of social issues which had emerged earlier.

Shonagh: If we put aside the animal rights issues surrounding fur for a moment, could I ask you to comment on how fur could be seen as a sustainable fabric? It is organic, and the pelt biodegrades. Did you find knowledge about this in your research?

Jonathan: Kopenhagen Fur gave me access to mink farms. The farms have all changed since COVID-19 and the decimation of the mink population. But at the time, going to see a mink farm—if you can get over any emotional or ethical reservations—is the perfect model of sustainability and circular economy. Once the mink skins are used, the carcass of the animal is used for other animal feed, the fat produced goes to make mink oil which is used in medical and cosmetic industries, and the waste products of the animal are converted into biofuel. Minks themselves are fed on the animal parts left over after food processing things like chicken nuggets and fish sticks; they eat all that rubbish. It's an entirely circular economy in terms of its farming and production.

Then the actual garment itself. As long as it's if it's been dyed using natural dyes, not synthetic or chemical dyes. And as long as any additions like buttons or linings that are non-natural are removed. A fur coat is a perfectly biodegradable object. So in that way, it is ultimately sustainable.

The other side to this, the more philosophical idea of sustainability. Is that a fur coat is typically an expensive item. So it tends to be kept and passed down from generation to generation. Or at least, it had been up until now—a solid anti-fur feeling is perhaps lessening this. The garment can also be modified. Many existing furriers, their leading trade today, is not selling new fur coats; it's adapting old ones into things. So if looked after and cared for properly, it has an incredibly long life span.

There is a problem with cheaply produced fur coats dyed with synthetic dyes; they would not biodegrade. Also, a lot of the less regulated farms produce a lot of excess waste and pollution. However, the farms that I visited were very well regulated and were subject to highly stringent controls, both environmental and veterinarian.

Shonagh: Then to look at it from an animal rights standpoint. When did the contemporary anti-fur movements come into being, and why did people get so angry? I had an experience, which I outlined in the introduction to this interview, where a man shouted "You are fucking ugly" at me in the street because I was wearing fur.

Jonathan: Some organizations, such as Lynx, grew out of Greenpeace. So there was a political collective idea forming which was part of many consciousness-raising movements of the 70s. Like the origins in the 19th century, I think we come to a similar moment in the 1970s when animal rights were part and parcel of a growing tide of anti-establishment feelings. The fur coat by then had become a symbol of the establishment. I think the particular kind of virulence that you're talking about; we can trace back to the formation of Lynx and PETA, who actively courted and used controversial campaigns to mobilize people. They have been highly effective.

What you explained in your own experience is something that I found particularly interesting because PETA especially has equated the idea of wearing fur with notions of sexual stereotyping. Being particularly outspoken against women in a somewhat perverse way. It becomes incredibly misogynistic. The women who wear fur in the campaigns are denigrated as ugly, stupid, or cruel. Yet, very rarely do they direct the campaigns against producers, manufacturers, or furriers. I know they might take physical action against furriers, but it tends to be women who are the targets in the campaigns. In their minds, women are seen as the primary consumers. There's an extraordinary kind of misogyny that has taken hold and become part of popular discourse that the guy in the street may display towards you.

In the book, I talk about some of the problematic campaigns they use and the outrage against them, not just against women but against particular minorities. But they feel that their cause is worth it by any means necessary.

Shonagh: It is even more interesting as historically, the fur coat was often gifted to a woman by a man.

Jonathan: It is a very difficult subject. I hope I make it clear in the book, I'm not advocating the wearing of fur by any means. But I am advocating understanding a broader history of the subject. We shouldn't shy away from speaking about something just because it is perhaps politically, ethically, or emotionally sensitive—this should be all the more reason to talk about it.

Shonagh: You also look into the history of fake or faux fur in the book. It has been around a lot longer, perhaps than some may think.

Jonathan: The earliest example I have in the book, which is debatable, is this Bronze Age hat found in a grave burial and dates back to 1365 BCE. When you look at it in detail, it is made from very finely knotted threads that give the impression of fur. Many experts in that period, far more expert than I, have suggested that this was a form of emulating fur that would have required so much skill and talent that it was more highly prized than real skin. Therefore, it was suitable for a warrior or whoever it might have been buried with. It's in a museum in Denmark.

In Tutankhamun's tomb, alongside the remains of real leopard skins, were fake leopard skins made of a kind of network lattice of beads with golden heads and claws. Leopards were assumed to be magical beings that, and in the afterlife, Tutankhamun would be able to assume their characteristics . So if you count those examples, fake fur has a history almost as old as fur itself.

The other aspect that predates the idea of fake fur, as we would understand it, is furs, pretending to be other furs. These garments aren't precisely fake or faux in the sense that they are artificial furs, but there's a long history from the medieval period onwards of the and a trade in furs being refurbished and disguised to look new. Linings were taken out of garments, new ones were put in, and more expensive furs were faked using cheaper furs. A typical example is ermine, which is the winter coat of the stoat. In the medieval period, there was a practice of using white squirrel skins, or the underbellies of squirrels, with the little black tips made out of black sheepskin. They would sew them in, so it looked like ermine.

Then moving quickly forward into the 20th century or late 19th century, with the advent of chemical dyes, it was possible to shade and color cheaper furs to look like more expensive ones. So you might get rabbit dyed and painted to look like sable. Seal was one of the earliest furs faked because the desire for sealskin and sealskin jackets was so great that imitation sealskin began to be developed, called plush seal—they gave it all sorts of fancy names, but it's really a form of velvet. This was extremely popular at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

As we know it today, proper faux fur was developed around the 1940s with the advent of other synthetic fabrics. A lot of it was the by-product of plush fabrics that were used in other industries, like synthetic fabrics used for producing paint rollers; it was found that if you split the cloth and cut it, it produces a very luxurious plush feel. That kick-started that whole craze.

Bronze Age ‘fake fur’ hat c.1365 BCE, Western Jutland, Denmark, made from intricately knotted thin threads to resemble fur. National Museum of Denmark

Shonagh: I want to ask you about the complexity surrounding faux fur. On the one hand, animal rights campaigners herald it as the answer, whereas on the other, it is incredibly damaging to the environment. Can you talk about this tension?

Jonathan: As I said, on one level, a well-regulated farmed fur produced using natural dyes is ultimately very sustainable. On the other hand, most fake or faux fur is made from modified acrylic, and as with other petroleum-based products, it is made from non-renewable sources. It is highly pollutant during its production, and often it releases microfibers upon washing. You don't wash a lot of faux furs, but some indeed are washable plush fabrics. A lot is going into trying to reduce the shedding of these microfibers because at the moment, what happens is when they get washed, those fibers go into the water system and end up doing a great deal of ecological damage. They're non-biodegradable.

We are in a moment where I suppose the fur industry, which feels incredibly threatened, is producing all of this data to suggest how non-ecological most faux fur production is. Then at the same time, you've got the anti-fur lobby, who are not only anti-fur because of animal rights issues and ethical concerns, but they are also rightly saying that in some fur production, there is a lot of kind of water pollution and chemical waste. They are almost at loggerheads.

At the same time, more and more Western fashionable designers are renouncing fur. So that is ringing the death knell of fashionable fur as we know it in the West. It is a very crucial moment.

I have another issue with faux fur, personally. I have a problem with people wanting to wear an imitation of something that ethically and emotionally they are opposed to. I don't understand why you would want to wear something that could be mistaken as real, something which you passionately believe is wrong. I have the same feelings about vegans wanting to eat sausages made from tofu. I don't understand if you are passionately anti-meat-eating, why you would want to eat products that simulate or pretend to be the things you despise. I can't get my head around it!

I've got no problem with synthetic fabrics in themselves; it'd be nice if they were less polluting. People who are working in faux fur, what they're doing is amazing. There are interesting experiments to do with collagen and other kinds of fibers that are away down the line from being produced. But I do think we need to get beyond calling them faux fur. We need to find names that are different because they are wonderfully new, inventive technological fabrics. But while we still call them faux fur, not only does it lessen the creativity and the technical skill used to produce them, but we are back to this kind of oppositional mode, and I think it's a dead end.

Shonagh: I want to ask you about your teaching. It is an interesting time to be teaching fashion history and theory—you teach fashion thinking at Winchester School of Art—can you tell me what approach you take? How do you teach students to be critical fashion thinkers?

Jonathan: In a broad sense, it's not so much about necessarily being critical of fashion, but I hope—or my ambition is—to help students understand the essential position of clothing, if not fashion, to our whole existence. Physically, intellectually, culturally, clothing and textiles, I believe, are central to how we make sense of our world and how we relate to one another as a form of communication—as a tactile experience of the real world and its structure. So the urgent issues today are very much part of what I would like to instil as a moment of fashion thinking.

In terms of sustainability, we need to think of fashion thinking as similar to the processes of making clothes themselves. You start with very little, or at least you start with cloth, or an idea, which is then fashioned into a kind of garment. But that same garment, or that same concept, can be unpicked and reassembled to make a completely different garment—a new something from almost nothing. In this way, it resembles the way we need to think about fashion itself, which should always be constantly changing, adaptable, renewable, and, crucially, surprising.

I'm passionate about understanding clothing in different areas—not just literally the physical garment but also in art, literature, film, and design history. I am a firm believer that it holds a central space in all of those different disciplines. To try and think fashionably is to think about fashion, as we understand it, as not only an object, but as a verb, i.e., to fashion or to make something, and to always make new ideas, always engage in new thinking. It is also understanding fashion’s often colonial, oppressive history, is part of a particularly Eurocentric point of view, however, if we look at clothing in other cultures, we can understand it, acting and serving very different functions.

Much like fur and how a lot of its history has become enmeshed in Eurocentric concerns, at the detriment to understanding it in a more global sense, we need to understand clothing in terms of its function. Fashion has many functions beyond a dormant kind of physical protection. It has a language we all speak, no matter where we are.

Shonagh: Thank you so much for talking to me. My last question is, what would your fashion utopia be? If you could put a new system in place tomorrow, what would that be?

Jonathan: One of the aspects that reminds me of the research I undertook for Fur was understanding this idea of proscription. I talked quite a lot about clothes rationing during times of conflict and what role fur had to play. So I've often thought of a system of clothes rationing, not unlike what we had in the Second World War, which I know is very proscriptive, and would be impossible, probably, to institute today. I guess it would be open to wide-scale corruption. But if we, for example, were only allowed to attain maybe one or two items of clothing each year, I think we might think more about what we need, want, and desire. So that's one slightly crazy utopian idea I had. If we were forced to be limited, and you could have one coat, one pair of trousers this year… Questions do come up: such as who would supply these? Another huge argument….

The flip side of this, a bit like fur as a luxury item, is the quality and creativity of bespoke couture garments which appeal to me aesthetically. But obviously, socioeconomically, is prohibitive for many people.

Also, I'm a firm advocate of what I used to call second-hand clothing, and now everybody calls vintage. I still often find the most variety and excitement in clothes from earlier periods. But this, of course, is subjective and relevant to one's age. Clothes that I might have worn the first time around when they were fashionable aren't so appealing to me as ones that I hadn't worn because they are older. My daughter might wear something from the 80s, which I wouldn't be interested in, but would maybe be attracted to something from the 1940s or 50s. I don't think any of that's a utopia. But it's an insight into my attitude to clothes, how I approach them.